A six—day coastal hike offers up the best of Cornish scenery, history and, of course, pasties

You’ll find the best Cornish pasties in all of Cornwall in Porthleven,” the walker told me, leaning on the bar of the Tinners Arms in the village of Zennor. With his walking stick propped against a stool, he was your stereotypical British rambler, and his unshaven and tanned appearance suggested that he’d been hiking for many days. He was probably a long-hauler, walking the full 630 miles of England’s longest footpath — the spectacular South West Coast Path.

You’ll find the best Cornish pasties in all of Cornwall in Porthleven,” the walker told me, leaning on the bar of the Tinners Arms in the village of Zennor. With his walking stick propped against a stool, he was your stereotypical British rambler, and his unshaven and tanned appearance suggested that he’d been hiking for many days. He was probably a long-hauler, walking the full 630 miles of England’s longest footpath — the spectacular South West Coast Path.

In a roller coaster of stunning scenery, the trail scales the tops of rugged cliff lines, descends into isolated sandy beaches where the only company for the walker are seals and gulls. It skirts the ruins of old tin mines, mounts numerous stiles over stone walls dating back to the Bronze Age, and drops each night into one of many traditional mining and fishing villages along the way.

The South West Coast Path is partly based on trails created by coastguards patrolling the area for the many smugglers that abounded in these parts up until the turn of the last century. For this reason, the path literally hugs the coast.

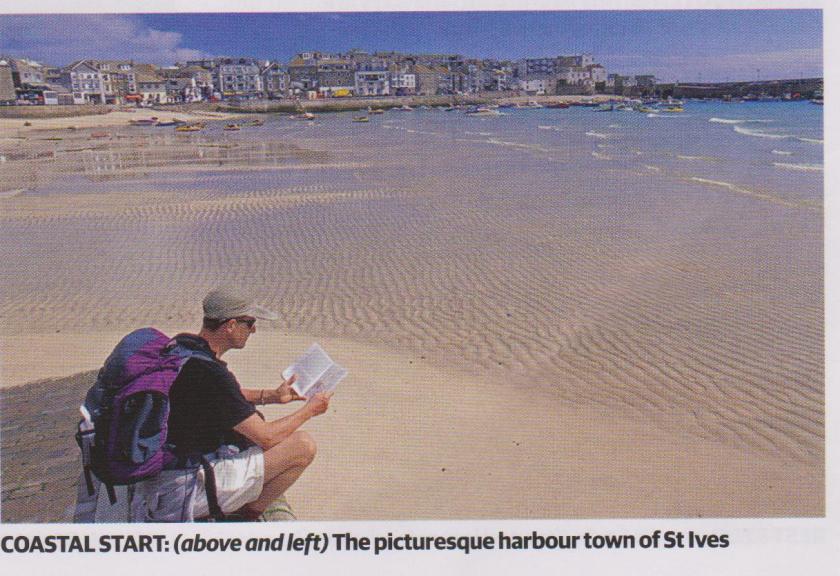

With limited time I’d chosen to walk the most scenic six day section, walking from St Ives, around Land’s End (Britain’s most westerly point) to Lizard Point (Britain’s most southerly point) — a total of 65 miles of Cornwall at its best.

With limited time I’d chosen to walk the most scenic six day section, walking from St Ives, around Land’s End (Britain’s most westerly point) to Lizard Point (Britain’s most southerly point) — a total of 65 miles of Cornwall at its best.

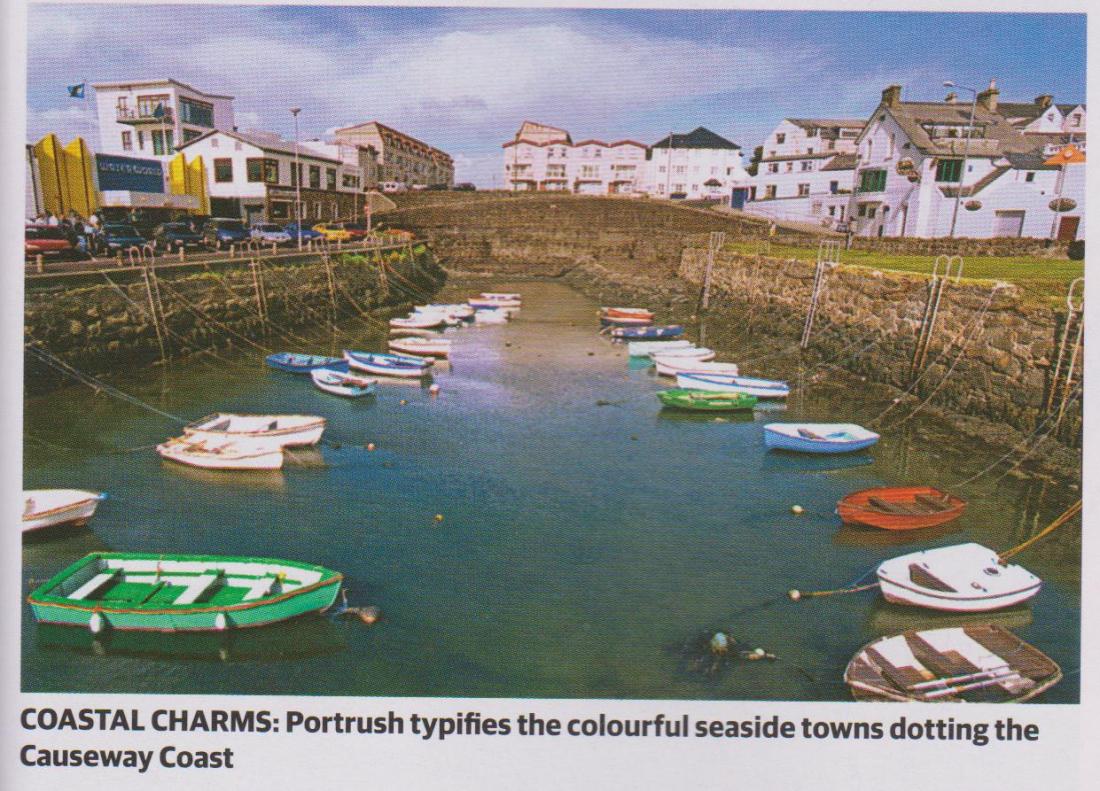

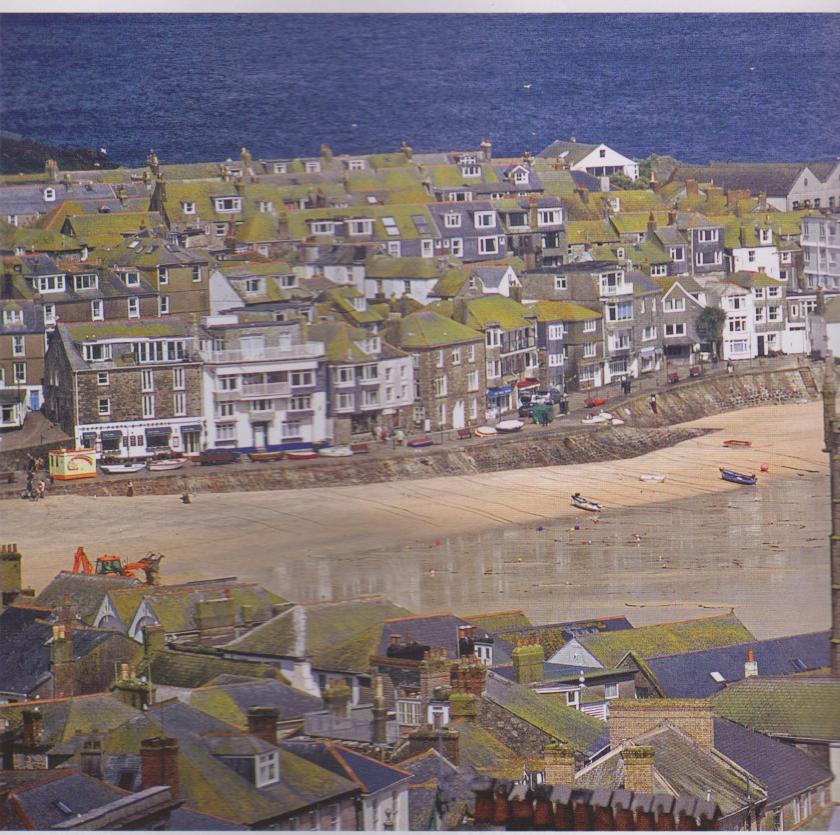

It was an early September day punctuated with the raucous cries of seagulls. Down on St Ives harbour side, amusement arcades rang with the sounds of one-armed bandit machines, while the sea air was tinged with the sickly sweet aroma of candyfloss and toffee apples. Colourfully painted fishing boats were just returning with the day’s catch, salty characters loaded off their catch of crab, kippers and had dock, destined for the town’s numerous fish and chip shops.

In the early sunshine, I walked along the waterfront, past the Three Ferrets where I had indulged in a celebratory few the night before and climbed up the steep road lined with terraced fishermen’s cottages out on to the coastal heathland above the town.

The sea breeze whipped the tangy scents of salt and seaweed into our lungs as I pulled away from St Ives. The views of the rooftops soon slipped beyond the farmers’ fields and hedgerows. A few miles further on the going quickly got tough. The trail began a series of plunging descents into rock-strewn coves and torturously steep ascents on to headlands offering panoramic views of turquoise waters below.

The sea breeze whipped the tangy scents of salt and seaweed into our lungs as I pulled away from St Ives. The views of the rooftops soon slipped beyond the farmers’ fields and hedgerows. A few miles further on the going quickly got tough. The trail began a series of plunging descents into rock-strewn coves and torturously steep ascents on to headlands offering panoramic views of turquoise waters below.

The secretive nature of this rugged coastline was perfectly suited to the nefarious trade of smuggling, which for centuries was a way of line in Cornwall. In the 1800s, it became a highly recognised business. Elaborate codes using flashing lights or fires were sent from strategic positions in the numerous coves to let smuggling vessels know of the whereabouts of the excise men.

While walking, I imagined the clandestine landing parties pulling their heavily loaded boats up the beach, to be met by the local residents who, in the dead of night were waiting to cart the contraband away. The clifftops above provided the perfect lookout for anyone approaching from either direction along the coastal pathway.

For my first morning, seven miles wasn’t bad start, and the Tinners Arms, the one-time home of DH Lawrence in 1916, provided a welcome lunch stop. You will get an eyeful of the old copper mines in the next two days and be sure to have a pint at The Star in St Just,” continued the walker in sporadic bursts between mouthfuls of fisherman’s pie.

“Well it’s all up and down from here to St Ives,” I replied. “And watch yourself around the badger’s sett near Polgassick Cove; it’s right on the path and big enough to fall into.” It was a typical exchange of walkers going in opposite directions on the path.

“Well it’s all up and down from here to St Ives,” I replied. “And watch yourself around the badger’s sett near Polgassick Cove; it’s right on the path and big enough to fall into.” It was a typical exchange of walkers going in opposite directions on the path.

By 7.30pm that first evening, after a marathon 18 miles to St Just, a B&B had never looked so good and a watering down at The Star was just the ticket to wash away the salt and lubricate my aching muscles. The first day set the scene for the days to come and the good weather continued. Blazing blue skies and no hint of the infamous fogs that can turn the clifftop trail into a treacherous trap.

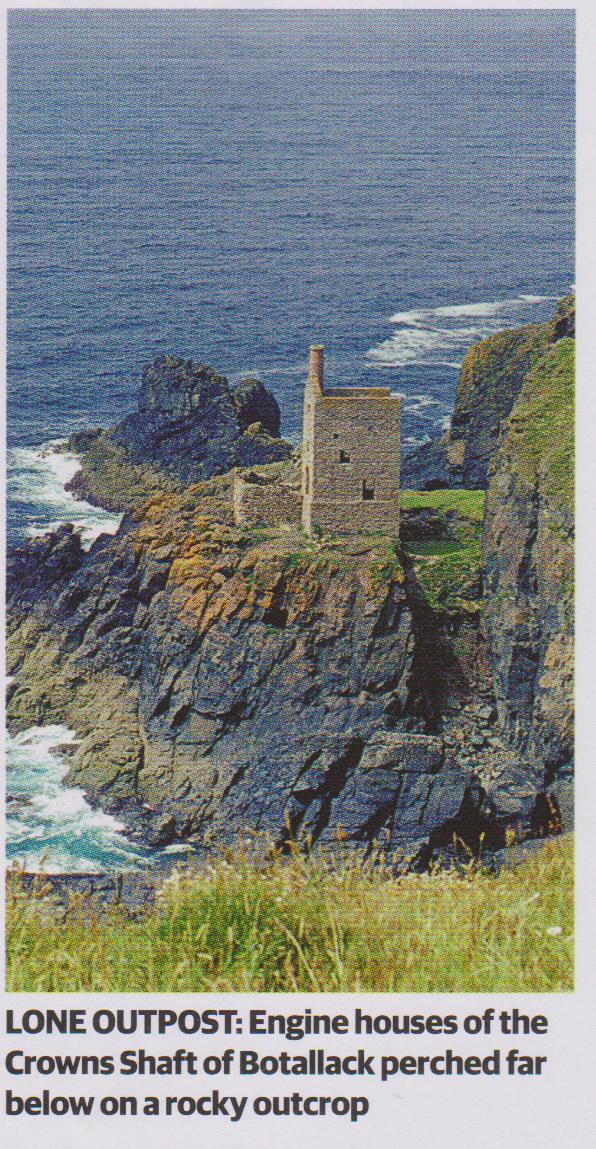

Day two offered everything the walker at the Tinners Arms had predicted. Like empty eye sockets, the windows of derelict mine pumping stations followed me as I strode past. Old chimneys pointed at the sky like bony fingers and mine shafts dug into sheer cliff faces disappeared into the depths of the earth.

The path skirted past the picturesque engine houses of the Crowns Shaft of Botallack perched far below on a rocky outcrop. The workings once stretched well under the sea and it was said that the miners could hear the boulders rumbling over the seabed above their heads. It was certainly a tough life in such a dangerous and wet environment.

The path skirted past the picturesque engine houses of the Crowns Shaft of Botallack perched far below on a rocky outcrop. The workings once stretched well under the sea and it was said that the miners could hear the boulders rumbling over the seabed above their heads. It was certainly a tough life in such a dangerous and wet environment.

Land’s End is a milestone and, for the British, this magnificent rugged headland marks the most westerly point of the country. For walkers, it is a paradox of beauty and ugliness, but, perhaps more significantly, it’s a left hand turn on the final stretch.

Peter de Savary’s theme park sits like an ugly white elephant on this iconic point. A vast river of cars streams into the car park, disgorging visitors set on having their photos taken under the famous signboard for a few quid. I felt a sense of smugness as I walked past the queue, continuing on my way.

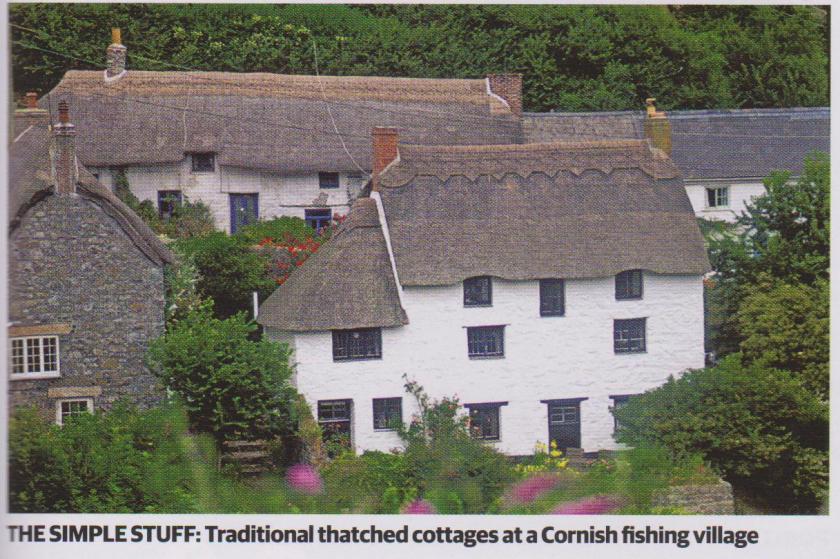

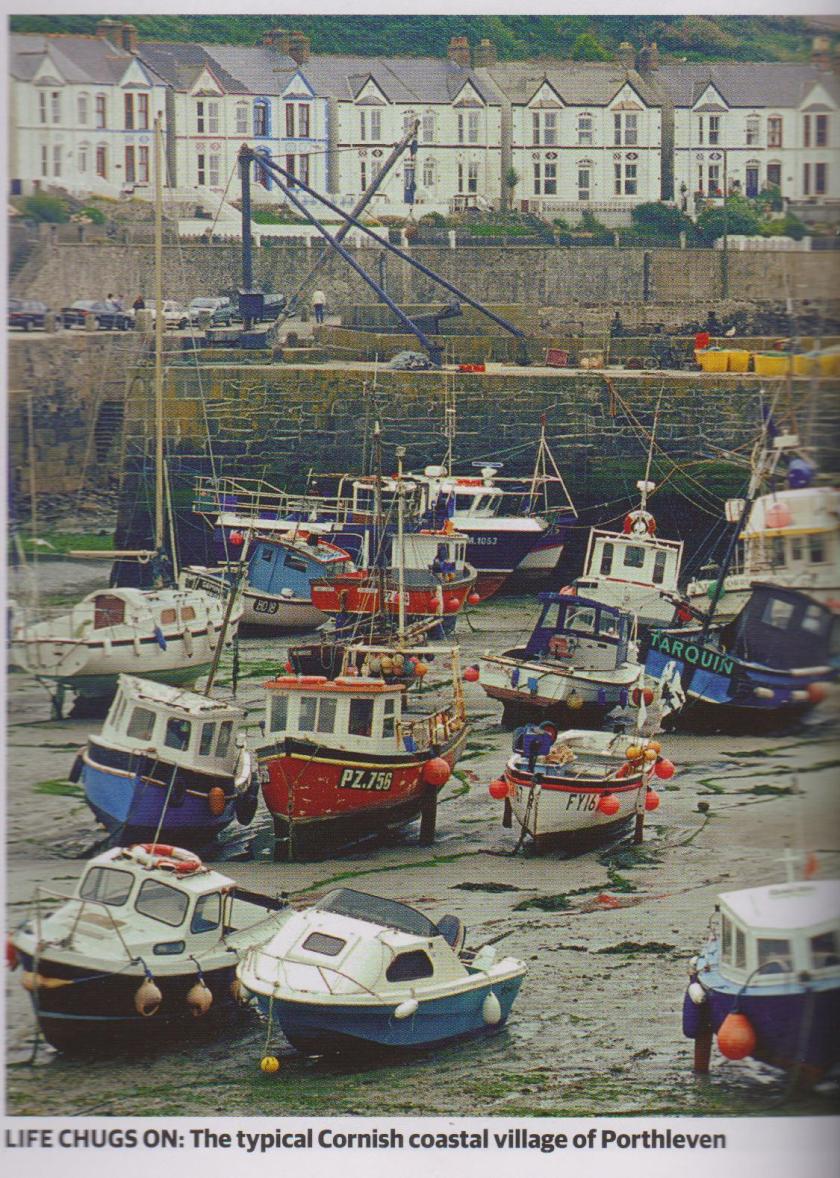

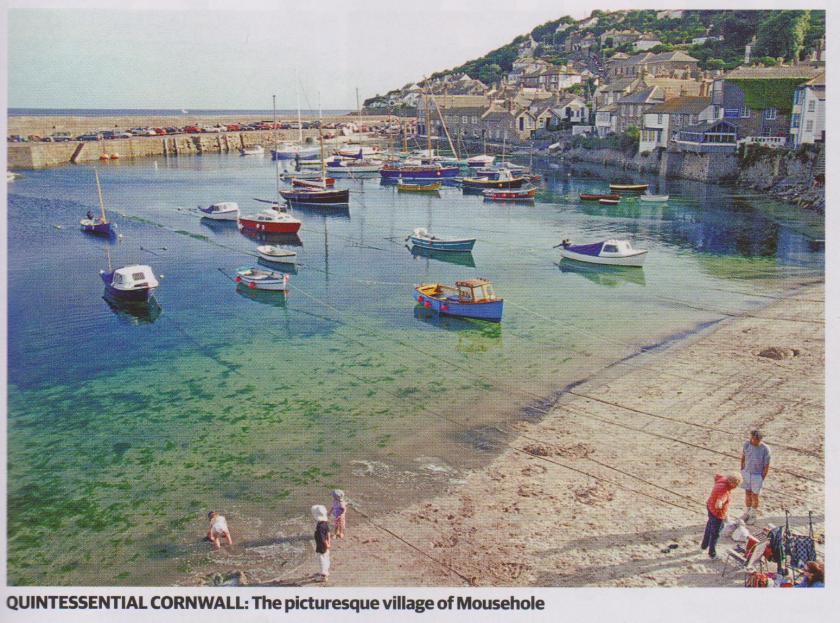

Although mining is the focus along the rugged west Penwith Coast, as I turned east, fishing took over and quaint villages punctuated the gentler terrain. Dropping into hidey-hole villages like Mousehole and Porthleven was a highlight and the promised Cornish pasties at the Porthleven bakery were beyond expectations.

Fishing has long been the mainstay of the economy and many of the towns have wonderful medieval harbour walls where an assortment of colourful boats lies at varying degrees depending on the tide. This is quintessential Cornwall at its most picturesque.

My last stretch was a gentle amble along grassy cliff tips, climbing over numerous stone stiles between fields with only a few steep plunges into wide sandy bays.

After only six days of walking, it was with a tinge of regret that I first caught a glimpse of Lizard Point. The freedom of literally tramping through a land rich with natural beauty and history was addictive. And as I climbed up on to England’s most southerly point, I was already plotting another six days further along the South West Coast Path.

Courtesy by K.T.